Electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all possible frequencies of electromagnetic radiation.The “electromagnetic spectrum” of an object has a different meaning, and is instead the characteristic distribution of electromagnetic radiation emitted or absorbed by that particular object.

The electromagnetic spectrum extends from below the low frequencies used for modern radio communication to gamma radiation at the short-wavelength (high-frequency) end, thereby covering wavelengths from thousands of kilometers down to a fraction of the size of an atom. The limit for long wavelengths is the size of the universe itself, while it is thought that the short wavelength limit is in the vicinity of the Planck length. Until the middle of last century it was believed by most physicists that this spectrum was infinite and continuous.

Most parts of the electromagnetic spectrum are used in science for spectroscopic and other probing interactions, as ways to study and characterize matter. In addition, radiation from various parts of the spectrum has found many other uses for communications and manufacturing (see electromagnetic radiation for more applications).

Range of the spectrum

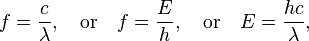

Electromagnetic waves are typically described by any of the following three physical properties: the frequency f, wavelengthλ, or photon energy E. Frequencies observed in astronomy range from 2.4×1023 Hz (1 GeV gamma rays) down to the local plasma frequency of the ionized interstellar medium (~1 kHz). Wavelength is inversely proportional to the wave frequency,so gamma rays have very short wavelengths that are fractions of the size of atoms, whereas wavelengths on the opposite end of the spectrum can be as long as the universe. Photon energy is directly proportional to the wave frequency, so gamma ray photons have the highest energy (around a billion electron volts), while radio wave photons have very low energy (around a fem to electron volt). These relations are illustrated by the following equations:

where:

- c = 299792458 m/s is the speed of light in a vacuum

- h = 6.62606896(33)×10−34 [[J·s = 4.13566733(10)×10−15 [[eV·s is Planck’s constant.

Whenever electromagnetic waves exist in a medium with matter, their wavelength is decreased. Wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, no matter what medium they are traveling through, are usually quoted in terms of the vacuum wavelength, although this is not always explicitly stated.

Generally, electromagnetic radiation is classified by wavelength into radio wave, microwave, terahertz (or sub-millimeter) radiation, infrared, the visible region is perceived as light, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. The behavior of EM radiation depends on its wavelength. When EM radiation interacts with single atoms and molecules, its behavior also depends on the amount of energy per quantum (photon) it carries.

Spectroscopy can detect a much wider region of the EM spectrum than the visible range of 400 nm to 700 nm. A common laboratory spectroscope can detect wavelengths from 2 nm to 2500 nm. Detailed information about the physical properties of objects, gases, or even stars can be obtained from this type of device. Spectroscopes are widely used in astrophysics. For example, many hydrogen atoms emit a radio wave photon that has a wavelength of 21.12 cm. Also, frequencies of 30 Hz and below can be produced by and are important in the study of certain stellar nebulae and frequencies as high as 2.9×1027 Hz have been detected from astrophysical sources.